What is Public Policy?

According to Wilson (2009), public policy is what governments decide to do, or not do, and their explanations for the outcomes of those decisions in the real world.

A recent example of this is the government’s 2019 cash injection into the mental health sector, where:

- The government identified mental health & addiction services as insufficient to meet the needs of patients.

- The government decided to address this by providing an additional $1.9 billion in funding to the sector.

The government decided that there was an unmet need for mental health and addiction services, and as such put it to the public as a problem that needed addressing. This is part of the first stage of a particular perspective on how governments make these decisions, called the policy cycle.

What are the five steps in the Policy Cycle?

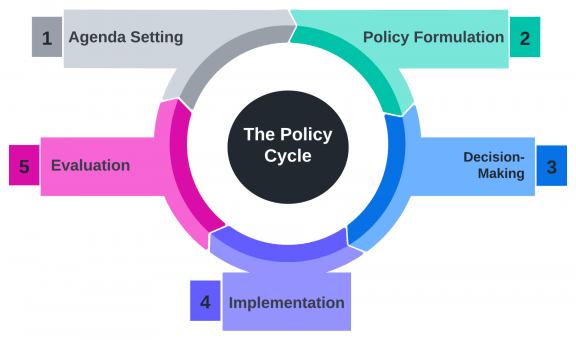

Laswell originally outlined the policy cycle in 1956, which at the time had seven stages. Since then, the stages within the cycle have evolved. Jann and Wegrich (2006) propose that the five ‘generally accepted’ steps of the policy cycle are:

1. Agenda setting

The first stage involves identifying a problem that requires government intervention, and proposing it as an issue to the public. We have already mentioned an example of this in mental health & addiction services, where the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction (2018) contributed to putting the inadequacies of mental health and addiction services on the public agenda.

Agenda setting represents a ‘laundry list of to-do items’ that the government is seriously considering (Kingdon, 1995). At this stage, no decision will have been made about how that a problem might be addressed, and whether that solution will ever be implemented.

2. Policy formulation

Now that the government has identified the problems it would like to address, it needs to decide how it will address them. The policy formulation stage is the setting of objectives based on a problem defined in agenda-setting, and consideration of alternative actions achieve those objectives (Jann & Wegrich, 2006).

There are a number of alternative perspectives on how this stage actually happens. These range from more general organisational decision theory (Olsen, 1991) to specific long term planning approaches for governments, like the Planning Programming Budget Systems from the US.

Specifically in regards to mental health & addiction services, actions to improve services were proposed in the He Ara Oranga inquiry into mental health, which included:

- Expanding the target for the proportion of the population that could access specialist mental health services at any given time from 3% to 20%.

- Adding specialist mental health services to primary health care.

- Establishing a mental health and wellbeing commission.

Now that the public agenda has problems to choose from, and solutions have been proposed, the next step is for government is to commit to a combination of the two in the decision-making stage.

3. Decision-making

The decision-making process is not an exclusively rational exploration of alternatives. Rather, it is a bargaining process by those with interests in the problem with the decision-making levels of government in order to advance those interests (Kenis & Schneider 1991).

In addition to the pursuit of and debate between different interests, there can be constraints over which problems can be selected and which solutions can be proposed. These can include budget and capability constraints (Jann & Wegrich, 2006).

Thinking about our mental health and addictions policy example, we may want to consider:

- Who are the actors in this policy problem?

- What are their interests?

- What constraints were applied to the policy problem?

- What constraints were applied to the solution?

- What was the selected solution as part of the ‘cash injection’? Were all the recommendations from the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction adopted?

4. Implementation

Once decided on, the proposed actions to solve the policy problem need to be implemented. O’ Toole (2000) describes the implementation as what happens between the government’s intention to act, and the impact of that action.

Jann and Wegrich (2006) propose that an ideal policy implementation should include:

- Clear solution details. For example, a clear interpretation of the solution and which organisations should be involved in implementing it.

- Clear allocation of resources to organisations involved in the solution.

- Clear delegation of decision-making authority.

Given our mental health & addiction services example, we may want to consider whether these 3 elements were included in the ‘cash injection’ in 2019.

5. Evaluation

How do we know whether we solved the policy problem? The final step in the policy cycle is to measure success.

Initially, we may consider rigorous, quantitative, scientific evaluation as the go-to approach here. However, the literature refers to a wider scope of evaluation activity in order to include values and assessments beyond the restrictions of traditional perspectives. Examples of these include opinions of the wider public, media and external audits of government departments (Howlett & Ramesh 2003).

For our ‘cash injection’ example, we may want to consider:

- How should we measure success?

- Who should be involved in that measurement?

- What should we do next if it is deemed to be a success?

- What should we do if it is not deemed to be a success?

It is also crucial that this stage may feedback into new periods of agenda-setting, decision-making and implementation, asking questions such as should the policy initiative be wound down, changed/improved, and/or continued. Now that we’ve explored the five stages of the policy cycle, it is important to consider assumptions within the cycles, critiques of it and alternative viewpoints around how policy is made.

What are some examples of these assumptions and critiques?

Assumptions within the policy cycle framework have been criticised. For example, the assumption that:

- People within government make decisions in linear, discrete steps (Sabatier, 1999). Research in psychology indicates that this may not be the case (Simon, 1947).

- The government can solve every problem it encounters (Wilson, 2009). This assumption shifts focus away from non-government-led solutions to policy problems, for example, from citizens (Ostrom, 2002).

Does this mean we disregard the policy cycle as a framework for thinking about public policy?

What does this mean for the budding Policy Analyst?

It is important to consider how our perspectives frame what we consider to be problems, what we consider solutions to those problems, and the steps for getting there.

We should also be mindful that case studies and models for understanding public policy may not provide the full picture of how the world really works. They often provide a simplified model of how the world works, and thus are useful because of this. The policy cycle’s longevity in the literature and research indicates its usefulness, despite its criticisms. It remains one way amongst many of understanding the policy process.

Test your knowledge

Want to learn more about public policy?

The Master of Public Policy is a 2 year, part-time, fully online, multidisciplinary programme which covers politics, economics, statistics and sociology to teach you the skills to develop effective public policy.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on content from POLICY 740, led by Dr. Sarah Bickerton and contributed to by Dr. Tim Fadgen. A special thanks to Dr. Bickerton for providing editing and oversight for this article.

References

Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction. (2018). He Ara Oranga. Retrieved from https://mentalhealth.inquiry.govt.nz/assets/Summary-reports/He-Ara-Oranga.pdf.

Howlett, M., and Ramesh, M. (2003). Studying Public Policy. Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems. 2nd Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jann W. & Wegrich, K. (2006). Theories of the Policy Cycle. F., & Miller, G. J. (eds.) Handbook of Public Policy Analysis (pp. 43-59). Taylor & Francis Group.

Kenis, P., and Schneider, V. (1991). Policy Networks and Policy Analysis: Scrutinizing an new analytical toolbox. In B. Marin and R. Mayntz (eds.), Policy Networks. Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Considerations, pp. 25–59. Frankfurt and Boulder, CO: Campus and Westview Press.

Kingdon, J.W. (1995). Agenda, Alternatives, and Public Policies. 2nd Edition. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers.

Lasswell, H. D. (1956). The decision process: Seven categories of functional analysis. College Park, MD:University of Maryland.

Olsen, J.P. (1991). Political Science and Organisation Theory: Parallel Agendas but Mutual Disregard. In R. Czada and A. Windhoff-Héritier (eds.), Political Choice. Institutions, Rules, and the Limits of Rationality, pp. 887–119. Frankfurt, M. and Boulder, CO: Campus and Westview Press.

Ostrom, E. (2002). Policy Analysis in the Future of Good Societies. The Good Society 11(1), 42-48.

O’Toole, L.J. Jr. (2000). Research on Policy Implementation. Assessment and Prospects. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 10, 263–288.

Sabatier, P.A., (1999): The Need for Better Theories. In P.A. Sabatier (ed.), Theories of the Policy Process, pp. 3–17. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Simon, H.A. (1947). Administrative Behavior. A Study of decision-making Processes in administrative Organizations. New York: Macmillan.

Wilson, R. (2009). Policy Analysis as Policy Advice. In R. E Goodin, M. Moran and M. Rein (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy. Oxford University Press.